Reconciliation has become the buzz word of the decade ever since the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) of Canada published their report on residential schools in Canada.* The TRC, headed by (then) Justice Murray Sinclair, heard from residential school survivors, families and native communities from all over Canada about their experiences in residential schools and their lives afterwards. These schools lasted for over 100 years, with the last one only closing in 1996.

Despite being called schools, residential schools were actually designed to separate native children from their parents, extended families and communities, for the express purposes of assimilating them into, what the TRC describes as “Euro-Christian society”. Thousands of children were starved, neglected, tortured, medically experimented on, mentally, physically and/or sexually abused or even murdered. Their experiences have had long-lasting, inter-generational impacts on many more thousands of children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

The TRC offered 94 Calls to Action directed to the federal and provincial governments, churches, businesses, the media, the public at large and, specifically, universities and colleges. The report went well beyond just the 94 specific Calls to Action – it also talked about reconciliation with native peoples generally. However, as is the case with many Royal Commissions, Public Inquiries and other similar reports, many Canadians never read them. The failure to read the TRC report, didn’t stop people from taking the word “reconciliation” and literally applying it to everything they do that touches on native issues and calling it “reconciliation”. I think reconciliation has gone off track.

To my mind, the word reconciliation should have substantive meaning; not just in the residential school context, but in the entire relationship between native peoples and the Crown. Firstly, it should be about exposing the whole truth of the genocide committed in Canada beyond residential schools. The TRC concluded that what happened in Canada was cultural genocide, but more than that, it was also physical and biological genocide. Canada needs to come to terms with that. It needs to come to terms with genocide in all of its forms, both historic and ongoing.

Secondly, reconciliation is about Canada taking full responsibility for this genocide.There should be no diminishing the experiences of survivors; no making excuses; no trying to justify what happened; no using semantics to try to downplay the atrocities committed; and no denying any of the harms suffered by native peoples. In any discussion about reconciliation, we should be centering the voices of the survivors and not the perpetrators, just like the TRC did.

Lastly, we can never get to real reconciliation without Canada making a real apology – not a court ordered apology, or carefully worded political apology approved by Justice lawyers. I mean a real apology where Canada:

(a) accepts responsibility for all of its actions and consequences;

(b) promises never to do it again, and in fact, doesn’t do it again;

(c) makes full amends for ALL of the harms done – which may include compensation, but is not limited to compensation.

Canada, in general, seems think that a political apology, coupled with meager monetary compensation and some commemoration is enough to ask all of us to move forward. There is a real problem with moving forward when the whole truth has yet to be exposed. If moving forward means skipping over the rest of the truth and focusing on superficial acts, like renaming National Aboriginal Peoples’ Day to National Indigenous Peoples Day, then we are very far away from reconciliation.

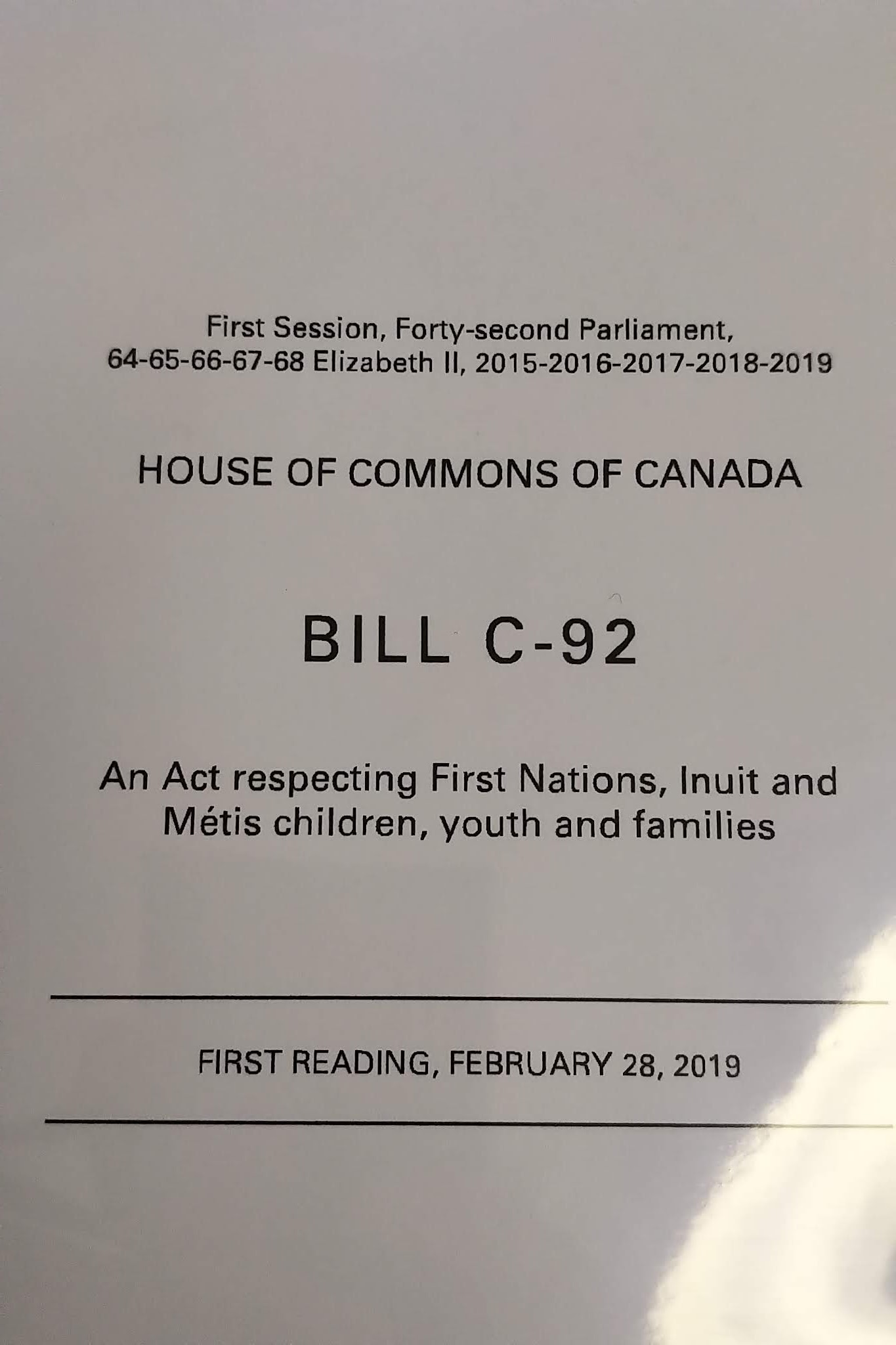

It is also incredible that Canada could even fathom moving forward when it has failed to stop the harms from continuing. For example, while the last residential school closed in 1996, this was followed by the 60’s scoop forced adoptions of native children into white families all over the world. That was then followed by the crisis of of over-representation in foster care. There are more native children stolen from their parents, families and communities today, than at the height of residential schools. In fact, the crisis of over-representation in foster care has even been acknowledged as a “humanitarian crisis” by federal officials.

When I say Canada, I want to be clear that I am talking about federal, provincial, territorial and municipal governments for sure; but also churches, Canadian citizens, mainstream media, corporations, businesses, universities and colleges. Every single person and institution in Canada has benefited from the genocide and dispossession committed against native peoples – either directly or indirectly. That makes lots of people uncomfortable to hear, but it is the reality. Most people have long thought that the so-called “plight” of native peoples was the responsibility of government alone – often willfully blind to their own roles.

Universities, colleges and training institutes in particular, have benefited directly from the dispossession of native peoples from their lands and sometimes benefited directly from Indian monies held in trust by the Crown. They have long excluded native peoples as faculty and administrators, while at the same time educating countless generations of Canadians and international students a sanitized version of both history and the present. Native voices and realities has been erased by universities for many decades. While it is very positive to see many universities and colleges embracing the TRC report and taking concrete steps to advance reconciliation, it has become very clear that there is a fundamental misunderstanding about what reconciliation really means in a university context.

The TRC called on universities and colleges to undertake the following:

Call to Action #16 – Create Aboriginal language degrees and diploma programs;

Call to Action #24 – Medical and nursing schools to provide a mandatory course dealing with Aboriginal health issues, which includes skills-based training in intercultural competency, conflict resolution, human rights, and anti-racism;

Call to Action #28 – Law schools to provide a mandatory course in Aboriginal people and the law with required skills-based training in intercultural competency, conflict resolution, human rights, and anti-racism;

Call to Action #65 – Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) and post-secondary institutions and educators establish a national research program with multi-year funding to advance understanding of reconciliation; and

Call to Action #86 – Journalism programs and media schools provide mandatory education for all students on the history of Aboriginal peoples.

However, it must be kept in mind that reconciliation goes well beyond those specific Calls to Action. Universities and colleges have a long way to go to address their role in the dispossession and oppression of native peoples – both historic and ongoing. However, I think this discussion needs to happen in reverse. Before I share some ideas about what universities should be doing to advance reconciliation, it may be more useful to look at some examples of what should NOT be considered reconciliation and why.

Not Reconciliation list:

(1) Apologize for university’s past contribution to oppression of native peoples;

(2) Give a land acknowledgement;

(3) Senior administration or professors attend a First Nation community or pow-wow;

(4) Hang native art on campus;

(5) Change street names or building names on campus;

(6) Partake in cultural sensitivity training or Aboriginal History 101;

(7) Watch documentaries like Colonization Road;

(8) Read Thomas King’s The Inconvenient Indian (I love this book);

(9) Send a First Nation or organization an email asking what you can do to help;

(10) Hire more native peoples to reflect our % of the population;

(11) Have an elder open and close your conferences;

(12) Nominate a native person for an award;

(13) Invite native faculty to sit on committees or Senate;

(14) Create an Aboriginal Advisory Committee on campus;

(15) Send a happy National Aboriginal Day tweet or Facebook post;

(16) Include First Nations in your research projects; and/or

(17) Invite native speakers into your classrooms.

There are many universities and colleges doing a number of the above items under the banner of reconciliation right now. Some may have even done some of these prior to the TRC report. However, I have seen a number of universities include some of these items in their reports on reconciliation. To my mind, none of these items fall under reconciliation. They are all important in different ways, and universities, should be doing these things, but they are not reconciliation.

Why not? Because most of the items on the above list should already be done in universities and colleges as a matter of law – as per federal and provincial human rights laws; employment laws; non-discrimination laws; equality laws; and campus commitments to diversity, equity and inclusion. Universities don’t get to pat themselves on the back for doing what they should have been doing all along under the law. Furthermore, some of the actions noted above should be happening as a matter of academic practice. If you teach about native issues, it should be a given that native voices and content are centered. It’s a matter of professional ethics and academic standards that faculty learn about the subjects they teach – or ought to be teaching.

The following represents a few things that universities should be doing under the banner of real reconciliation:

Real Reconciliation:

(1) Ensure that you hire native faculty and staff that reflects plus 20% extra hires to build institutional capacity; provide support for new hires; and to make amends for having excluded native peoples for all these years;

(2) There should be proportional (20%) native hires in ALL faculties and departments, especially politics, law, science, engineering, medicine and business (in addition to social work, midwifery & native studies);

(3) Do NOT ever hire just one native faculty member at a time. That is an incredibly unfair burden to that faculty member as everyone, even with the best of intentions, will want their advice, guidance, ideas and participation of that one faculty member on every committee, project and initiative;

(4) When you hire, you must develop workloads and expectations around the fact that many First Nation hires will have community-based expectations/obligations that should be accommodated.

It is their connection to their First Nations, their knowledge exchange and community-based work that often informs who they are, how they teach and what they teach.That unique knowledge and experience comes with commitments to their home communities which takes time and energy and should be accommodated and counted.

(5) Don’t stop at recruitment and hiring of native faculty and staff. Think about what your institution does to KEEP them there, i.e., professional supports, active mentorship, recognition, research dollars, promotions, pay levels, leadership opportunities, advanced training and skill development and flexible or alternative work arrangements. (6) Keep current commitments to native faculty and staff. For example, if you have a Chair in Traditional Native Medicine, make sure that Chair is made permanent, funded from core university dollars and not dependent on external funders (i.e., supported only if the funds are available). Making reconciliation initiatives dependent on the goodwill of corporate funders puts them all at risk given the fact that native peoples are largely discriminated against in the corporate world. Universities must engage in real sacrifices – of power and wealth – in order to engage in real reconciliation. That means the university itself must dedicate and protect the funds for reconciliation initiatives – includes faculty, staff, chairs, research and projects.

(7) Real reconciliation is about more than who teaches, it also requires that native peoples also be represented in the governance and senior administration of universities and colleges – as Presidents, Provosts, Chancellors and on boards of governors. They must be part of the decision-making mechanisms throughout the institution – including in the unions, committees and Senate, on all issues, but especially those that impact native peoples specifically.

(8) Native peoples need to be the ones deciding how targeted native research funding is distributed; who gets research chairs in native issues; and how academic success is measured – that means including the community-based work and advocacy that is an inherent part of the lived personal and professional realities of many native peoples.

(9) First Nations and Inuit communities need to have a direct line of input into university programs, curricula, research and governance that impact them and their students. It is not good enough to have one native faculty or several native staff members speak for diverse Nations. The relationship needs to include voices inside and outside the institution.

(10) Every university and college sits on native territory should reflect local native languages, cultures and symbols throughout the campus, in ways that are directed by native peoples (with a focus on local native communities) and respectful of their cultures. It is not good enough to have just one dedicated “native” area – like a statue, park bench or student centre. Our presence must be reflected throughout the campus(es).

(11) The benefit and privilege of a university education and research needs to be fully shared with local First Nations, with more focus on open access to information and publications and translation of research in accessible formats for community use.

(12) Universities need to think about education beyond tuition-paying students and include strategic partnerships and alliances with native communities to help fill research, policy and/or technical gaps that exist due to chronic under-funding and failure to implement treaties, by building these requirements into courses and research or special projects. (13) Universities could help make amends for past harms. Take for example, the crisis of disappearing native languages. Universities and colleges in partnership with native communities, elders and languages speakers, could help prevent native languages from extinction. Together, they could develop comprehensive k-12 education, as well as community-based native language instruction, to try to undo the devastating impacts of Canada’s assimilatory policies and the university’s roles in it.

(14) Universities need to ensure that their reconciliation plans are co-developed by native communities and experts – which may include faculty, but also those external to the university that are not at any risk of retaliation or ostracization. Without native peoples directing the path forward, universities risk of forging ahead with superficial plans, or replicating the status quo. (15) Universities must also focus on the recruitment, retention and support of native students towards academic success. This includes not only a welcoming atmosphere, various student supports like housing and grants, but also native faculty advisors, native courses, and special research projects and other opportunities. (16) Universities must take active measures against the growing trend of rushing to hire “self-identified” native peoples who are not native, not connected to community and have no lived experience as a native person. Universities are being flooded with those making false claims and universities commit further harms to actual native people by taking no action to prevent it from happening. When frauds take our places in universities as students, staff or faculty, our voices are once again erased and our identities over-shadowed by white ethnicity shoppers whose only claim to Indigeneity is ancestry.com or some distant relative from 400 years ago. At best, these frauds skew our numbers and taint our research, and at worst, they proactively work against real native peoples.

(17) Universities must find ways to prevent Deans from using the same old racist tactics, like using so-called “merit” versus “diversity” as a way to keep native people out of universities. This perception of merit is very biased and often used in racist ways to discriminate against native peoples. It has been used to keep women out of the boardroom and with lower salaries. It has also been used by non-native Deans to keep native peoples out of tenure-track positions. Even after the TRC report, I have still seen Deans revert to this racist form of excluding native peoples – as if their traditional Indigenous knowledges, their professional experiences, their community-based work are not valued the same as a non-native’s traditional educational background as “merit”.

There is a lot to do and it will require a fundamental shift in both thinking and practice. It will require real changes – a transfer of both power and wealth. This requires that universities make sacrifices to make space for native peoples – not simply Indigenize here and there. Universities can’t simply tweak their current structures and expect substantive results. Clearly there is a great deal that university can and should be doing. This blog is already too long to include a much longer list. I truly believe that some of this will happen in short term, and some of it will take a little longer. But without real native people at the helm – directing the path – it runs the risk of preserving the same status quo or worse. I believe that we are at a turning point. The TRC has helped jump start both conversation and action at the university and college level. We just need to ensure the way forward is co-developed by native peoples and communities, together with universities and colleges. We have a real opportunity to make lasting, impactful changes. Let’s move beyond the superficial and engage in real, transformative reconciliation now – which will mean doing things as they haven’t been done before. We’re ready academia – are you?

For those who prefer audio, here is a link to my Warrior Life podcast based on this blog: https://soundcloud.com/pampalmater/indigenous-reconciliation-in-university-and-colleges For those who want more information, here is a link to my Woodrow Lloyd Lecture on Reconciliation at the University of Regina in 2018: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=89s3l2mYGWg&list=PLDnK0xT7aXRBut5qi5rlJrDQWpS-Pxu1v&index=2&t=3083s

*This blog is based on a much longer speech that I delivered in Halifax for the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives in 2018.